Re-Vision

What is the need for mental health and climate change to permeate each other’s isolated, expert-led discourses? What is the paradigmatic change needed in conversations of CLIMATE CHANGE, MENTAL HEALTH, and their INTERSECTION? How does privileging voices from the margins inform mental health and climate change? How does climate justice shape mental health understandings of vulnerability and resilience?

-

Building Solidarities: Climate Justice and Mental Health

Raj Mariwala and Saniya Rizwan

-

Locating Adivasi Self within Environmental Justice

Alice A. Barwa

-

Indigenous Climate Justice

Kyle Hill

-

Women with Psychosocial Disabilities

Asha Hans

-

Caste, Climate (In)justice, and the Dalit Distress

Prashant Ingole and Camellia Biswas

-

Civic Spaces in Times of Climate Crisis

Dr. Garret Barnwell

-

Climate Anxiety: An Illness of the System

Ayisha Siddiqa

Context

How can climate-related mental health engage with difficult conversations of DELIBERATE POWER EQUATIONS rather than viewing both mental health and climate consequences as natural givens? In which ways do identities of caste, nationality, ethnicity, religion, gender, ability, occupation, class mediate between ‘risk factors’ such as drought, overgrazing, floods, earthquakes, and the intensity of their implications? How can conversations of therapeutic care go beyond clinician rooms to policies of rehabilitation, citizenship, livelihood security, public healthcare and housing?

-

Songs Of The Forest

Dayamani Barla

-

Climate Injustice

Kusala Wettasinghe

-

Weathering the Storm: Disability, Climate Change, Mental Health

Candice D’souza

-

Women of the Rivers of South Asia

Chhaya Namchu

-

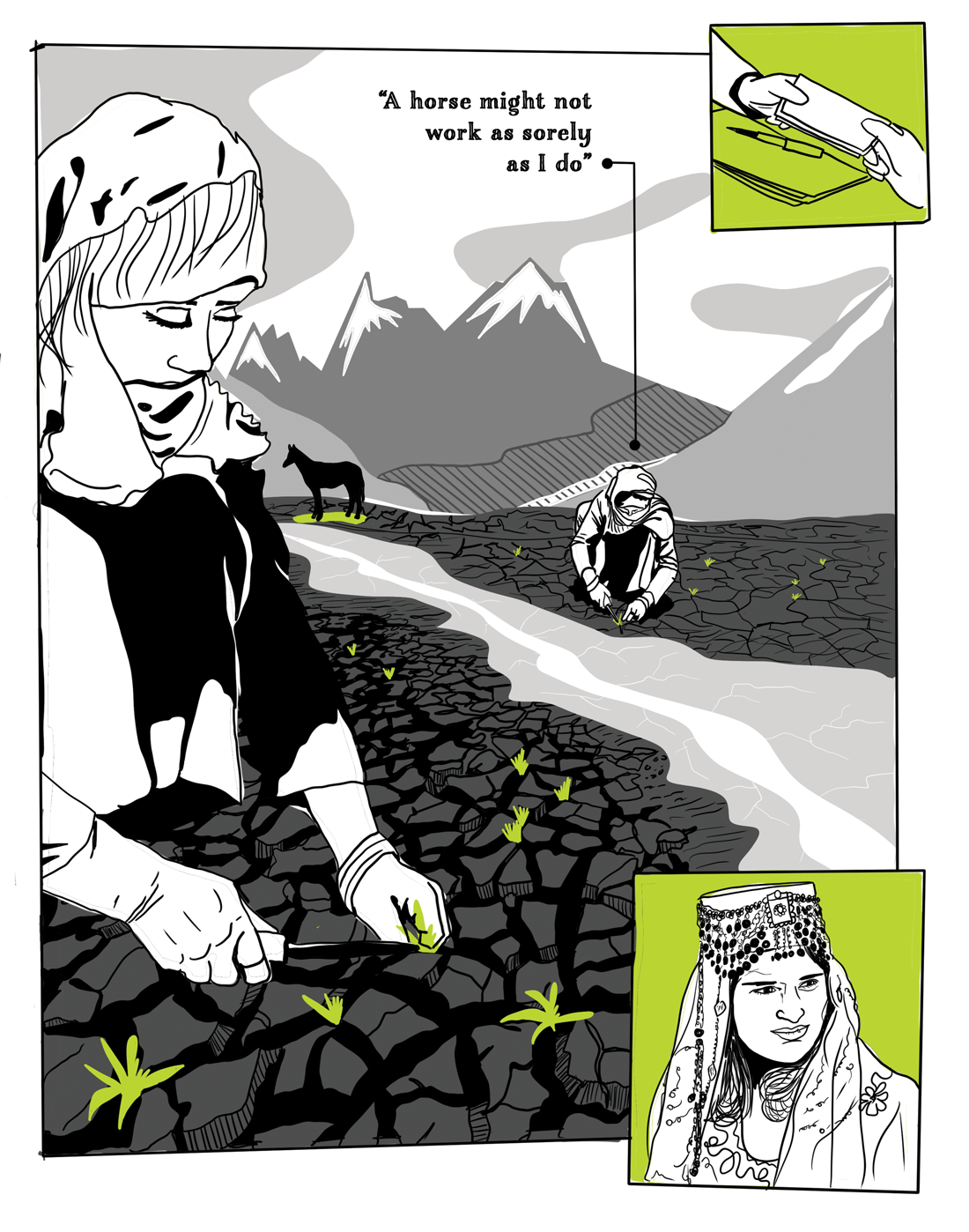

Climate Change at the Cost of My Life

Ahmad Nisar

-

Climate Justice implies Inclusive Justice

Abhishek Anicca

-

Changed Destinies in the Eastern Himalayan Region

Rituraj Phukan

Engage

What are the required considerations and target outcomes to keep in mind, while designing preventive policy and rehabilitative services and programmes for CLIMATE RELATED DISTRESS? How do we envision mental health care in policy and services for climate induced distress? In both community care and clinical intervention, how can we incorporate a rights-based lens and respond to structural climate trauma?

-

Mental Health In The Darjeeling Himalaya Socio-Ecology

Roshan P. Rai, Michael Matergia and Rinzi Lama

-

Memories of ‘Floods’, ‘Erosion’, and ‘Displacement’

Olimpika Oja

-

Environmental Health and Care Require Environmental Justice

Dulari Parmar, Manasi Pinto and Roshni Nuggehalli

-

From Collective Trauma to Collective Action

Manshi Asher

-

Troubled Waters

Dr. Manoj Kumar and Dr. Meena Nair

-

Is it a Good Time to Bring a Child into this World?

Jahnabi Mitra

-

Working for Disabled People’s Organisation of Bhutan

Ngawang Choden

MHI’s Work Innovation | Insights | Philanthropy | Challenges | Lived Realities

We work with multiple stakeholders, including non-profit organisations, governments, mental health professionals, and activists in the pursuit of an INCLUSIVE mental health ecosystem. Our core strategies include ADVOCACY, CAPACITY BUILDING, GRANTMAKING, KNOWLEDGE CREATION, and TRAINING.

About MHI

MHI provides grants and strategic support to organisations and collectives working within communities to provide greater access to mental health services for all.

About ReFrame

Reframe is a mental health journal that is published annually, covering broad, novel themes in this ever-changing landscape of mental health in India. Deliberately centred on the south asian experience, Reframe aims to be a global, internationally recognised platform for mental health from a south asian perspective.

PERMISSIONS: Copyright © 2022, Publisher: Mariwala Health Foundation CONTENT WARNING: Mentions of eco-anxiety, solastalgia, climate-induced distress, Islamophobia, homophobia, suicide, sexual violence, homicide, casteism and caste violence, race, rape, acid attacks, child abuse, colourism, ableism, domestic violence, eating disorders, chronic pain, trauma, mourning, forced migration, acute stress, intergenerational trauma, racism, oppression, confinement, physical trauma, confinement, blackmail, threats, sex trafficking, dysthymia, depression, PTSD, anxiety, communal riots and religious violence, state-imposed curfews and somatic symptom disorder. In the case of material being triggering or upsetting, you can reach out to icall at +91 9152987821 or icall@tiss.edu

EDITORIAL TEAM

Meenal Rawat

Olimpika Oja

Priti Sridhar

Raj Mariwala

Saniya Rizwan

COPY EDITOR

Shraddha Mahilkar

Shruti Nambiar

PROOFREADING

Amalina S

Olimpika Oja

Shruthi Murali

IMAGES

climatevisuals.org/ | wikkicommons | unplash.com

TYPEFACES

Freight by Joshua Darden

Neue Haas Grotesk by Christian Schwartz, Max Miedinger

ICONS

The Noun Project

MAP

DESIGN

Studio Ping Pong

studiopingpong.com