The National Highway connecting my hometown to Guwahati was home to thousands of marooned families for several weeks this year. Men, women, and children were forced to live on the road for weeks, sharing their space with livestock and companion animals, the shacks clearly insufficient to provide any protection from the periodic thunderstorms. One side of the highway was barricaded after a person was run down while he was having dinner. I was dismayed by the helplessness of these women and children; the lack of toilets and privacy exposed them to indignities unimaginable in this modern era.

Last year, a global survey of 10,000 young people across 10 countries revealed “profound psychological distress” attributed to the climate crisis, with anxiety and distress affecting daily life and functioning, worsened by perceived government inaction. Most respondents from the Global South including India and the Philippines were concerned about the “frightening” future.

Previous studies have shown that psychological distress about climate change exists, with affective, cognitive, and behavioural dimensions, and that such natural disasters have long-lasting effects on mental health and consequences including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and general anxiety.

Floods are expected annual occurrences, but I have seen the frequency and intensity increase since my childhood. This year, the first wave of floods in May was unexpected, with the heavy rains and landslides devastating the hill district of Dima Hasao and other areas with the loss of over a 100 lives. For millions of children, repeated waves of floods, landslides, and erosion will lead to innumerable loss of school days and, sometimes, the total end of schooling and any hopes of a better life.

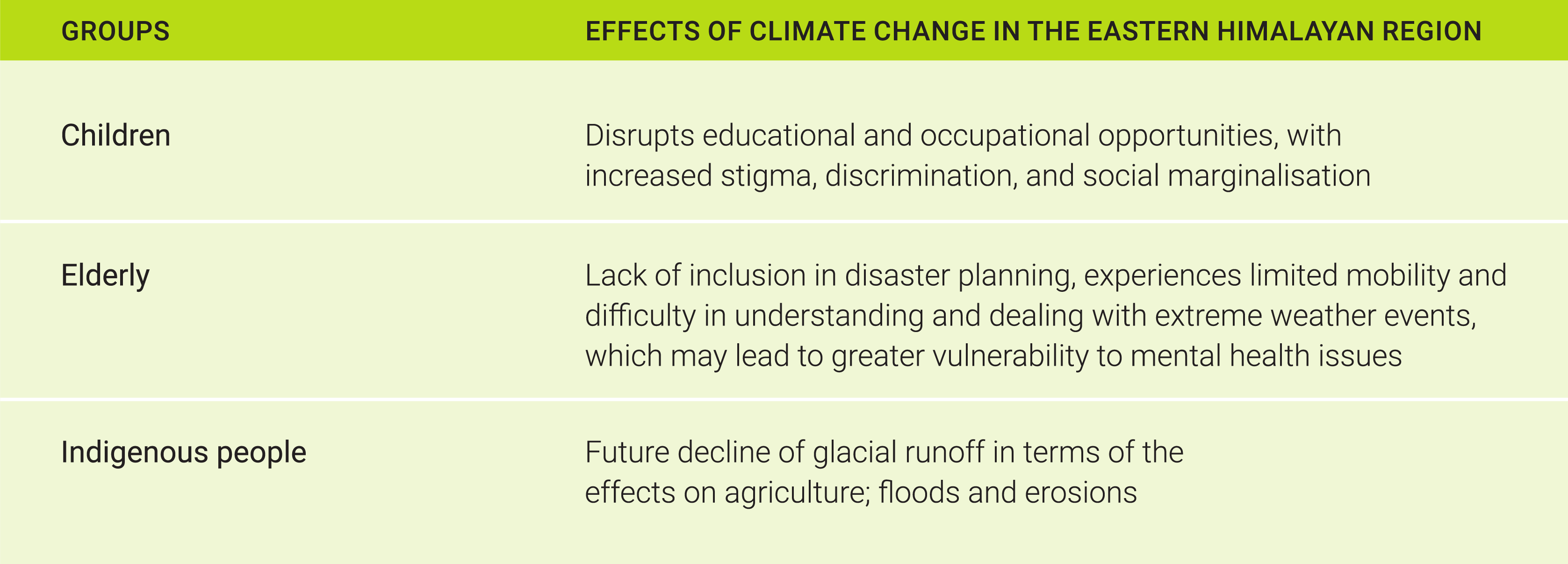

Studies have found that specific groups like children, the elderly, women, people with pre-existing mental illness, the economically disadvantaged, and the unhoused are at higher risk of distress and other adverse mental health consequences from exposure to climate-related or weather-related disasters. As climate change undermines children’s mental health, it disrupts educational and occupational opportunities, with increased stigma, discrimination, and social marginalisation. These evident consequences across the region need to be documented for targeted responses and remedial measures.

ISSUE NO. 5 DECEMBER

THE MARIWALA HEALTH INITIATIVE JOURNAL

Re-Vision

Context

Engage

Mental Health In The Darjeeling Himalaya Socio-Ecology

Memories of ‘Floods’, ‘Erosion’, and ‘Displacement’

Environmental Health and Care Require Environmental Justice

From Collective Trauma to Collective Action

Troubled Waters

Is it a Good Time to Bring a Child into this World?

Working for Disabled People’s Organisation of Bhutan