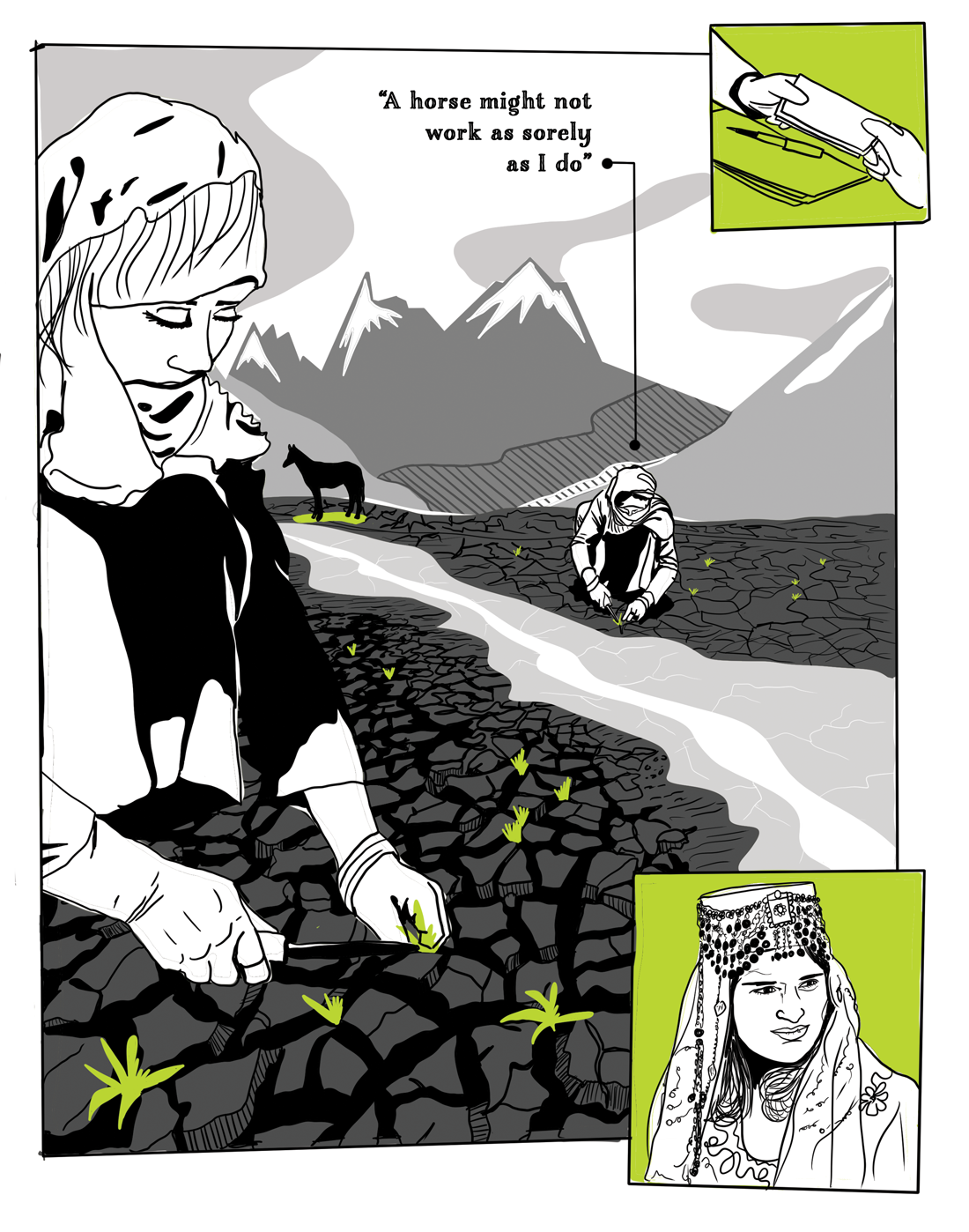

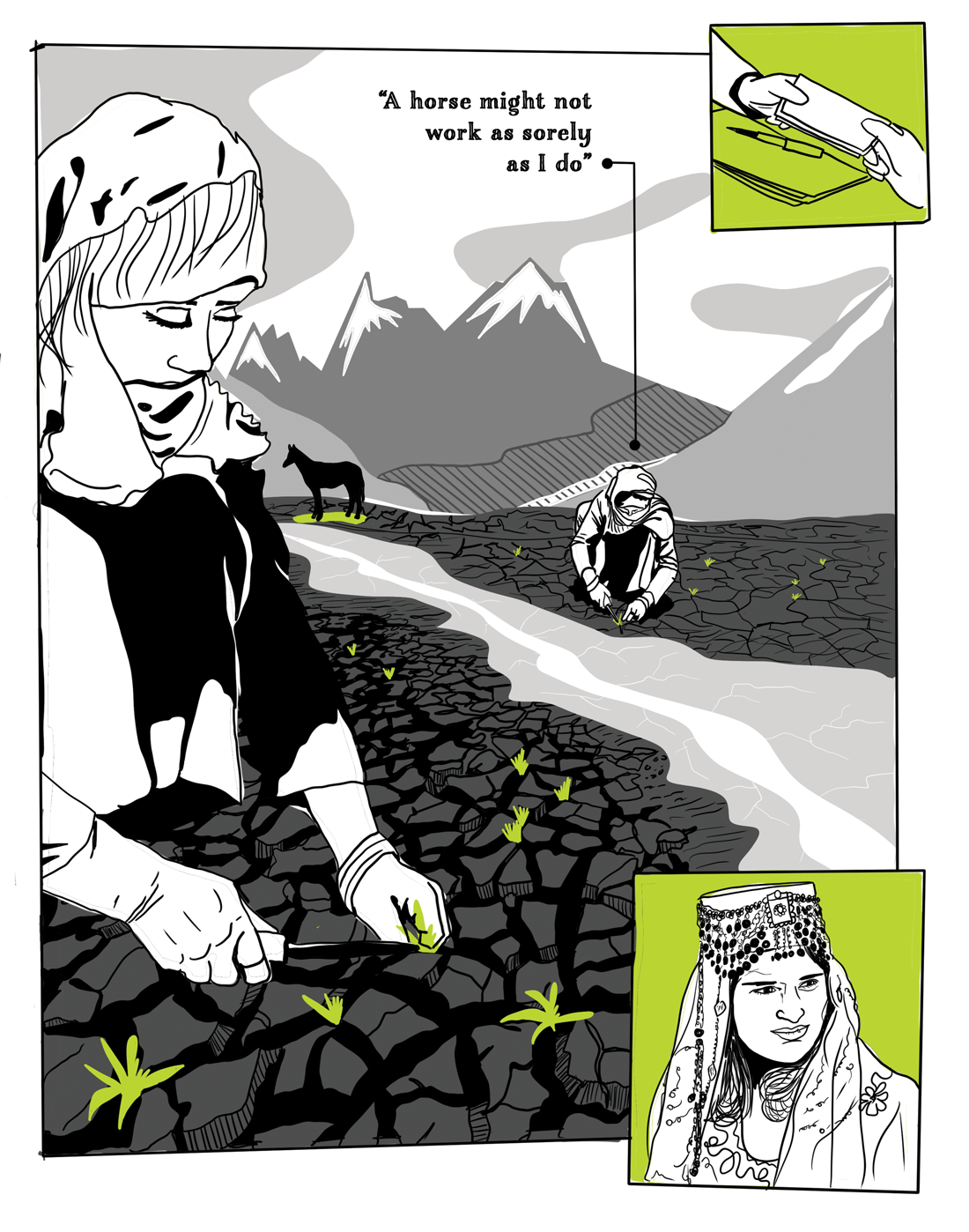

Afghanistan, home to 40 million people, faces enormous challenges of terrorism, political instability, and illiteracy. On top of these, Afghans are set to welcome another challenge – climate change! Over the last 3 decades, temperatures rose significantly (by 1.2 Celsius), droughts doubled, and over 14 percent of the total area of glaciers was lost. In the absence of preventative measures, future projections show that snowfall would diminish in the central highlands, potentially leading to reduced summer flows in the Helmand and Northern River basins, while spring rainfall would decrease across most of the country. Additionally, it’s predicted that in small pockets of the south and west, there might be a 5 percent increase in “heavy precipitation events” that can lead to flash floods.

The continuation of excessive garbage, industrial activities, and lack of awareness is confronting residents with previously non-existent diseases. Gaining deeper insight into the roots of climate change makes us comprehend that its reinforcing notion is poverty merged with a lack of policies and investment. As the government is laser-focussed on solving political dilemmas, they wouldn’t bother paying attention to the catastrophes climate change entails.

ISSUE NO. 5 DECEMBER

THE MARIWALA HEALTH INITIATIVE JOURNAL

Re-Vision

Context

Engage

Mental Health In The Darjeeling Himalaya Socio-Ecology

Memories of ‘Floods’, ‘Erosion’, and ‘Displacement’

Environmental Health and Care Require Environmental Justice

From Collective Trauma to Collective Action

Troubled Waters

Is it a Good Time to Bring a Child into this World?

Working for Disabled People’s Organisation of Bhutan