On some days, I close my eyes and imagine a couple seated in my chamber for therapy, talking about how worried they are about their 4-year-old’s access to the city and why she thinks aborting her next child is best for both. The husband looks grimly at the marine reef centre table between us and says, “I feel so guilty for the carbon footprint I have left behind. Had I taken more accountability in my youth, I feel we could’ve kept this child.”

This fragment of my imagination is part close to reality and part impending future. While technologies of freezing fertility and the extreme emphasis placed on romance among couples have impacted childbearing and family systems across the globe, climate change anxiety has also started to penetrate couples’ psyches in recent times.

ISSUE NO. 5 DECEMBER

THE MARIWALA HEALTH INITIATIVE JOURNAL

Re-Vision

Context

Engage

Mental Health In The Darjeeling Himalaya Socio-Ecology

Memories of ‘Floods’, ‘Erosion’, and ‘Displacement’

Environmental Health and Care Require Environmental Justice

From Collective Trauma to Collective Action

Troubled Waters

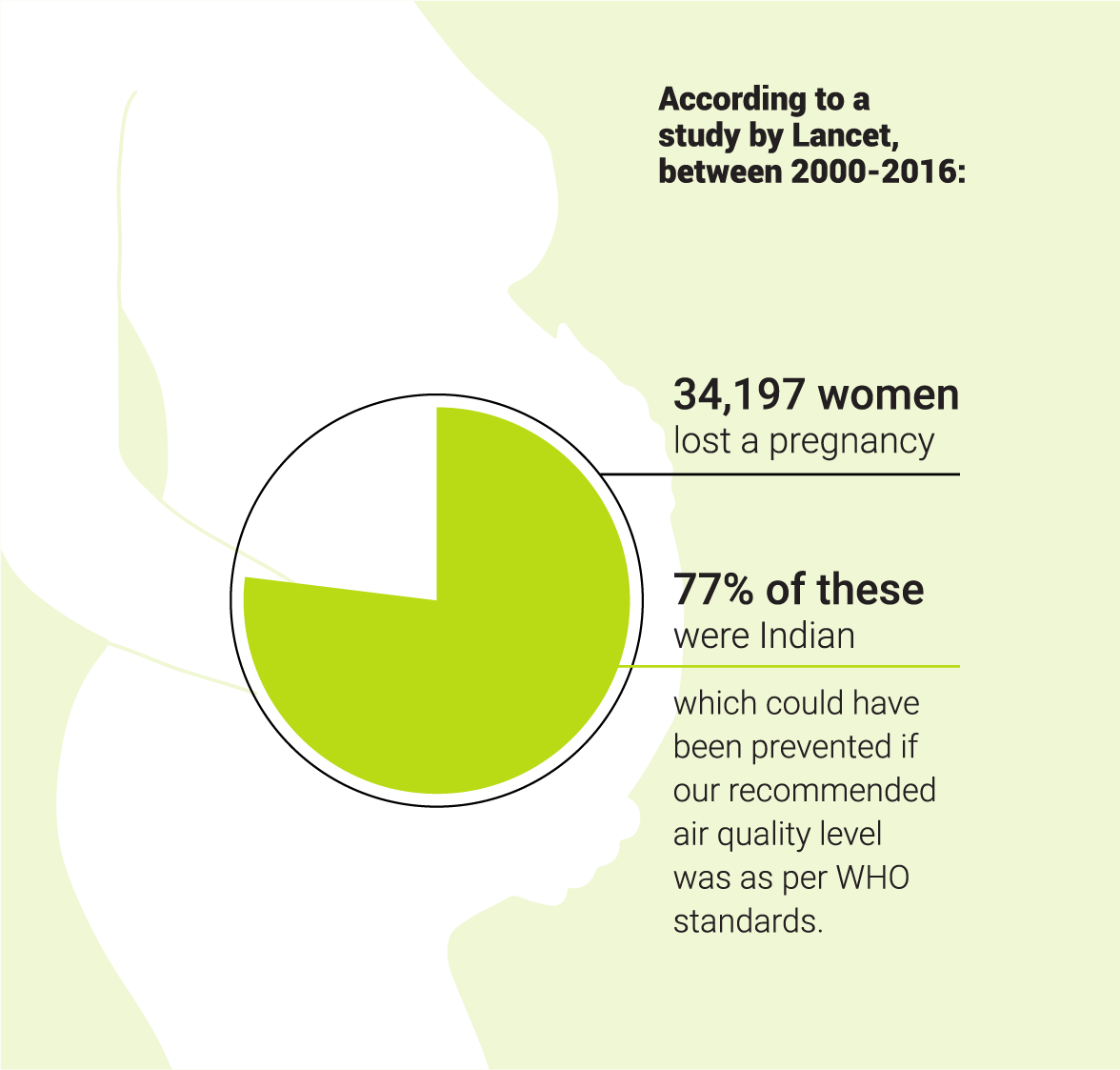

Is it a Good Time to Bring a Child into this World?

Working for Disabled People’s Organisation of Bhutan