Among the many urgent issues of contemporary times, climate change and mental health have garnered much attention over the last few years. Both have been given space in international diplomacy summits, national legislatures, and academic circles. However, the discourses on climate change and mental distress are currently overlooking the interlinkages between the two arenas as well as their need to intervene in each other’s isolated spheres.

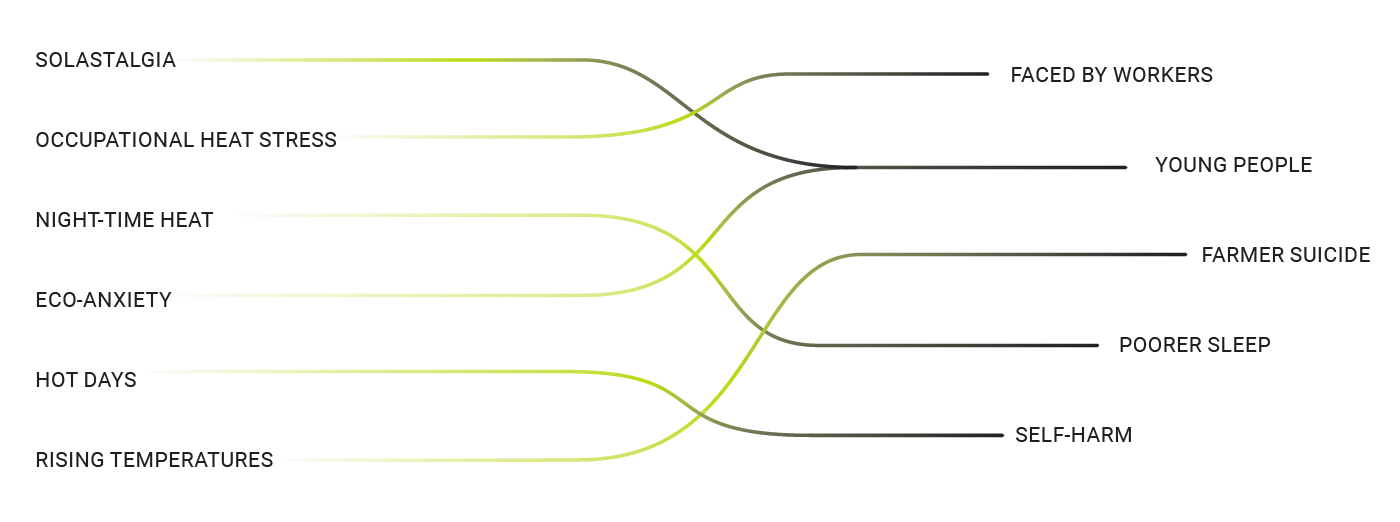

Climate change emergencies are deeply linked to psychosocial distress and structural oppression. Night-time heat is associated with poorer sleep, leading to deteriorating mental health. Hot days have shown links with self-harm. Rising temperatures have been correlated with farmer suicide. There are documented effects of occupational heat stress faced by workers. Mental health academia and literature explore the concepts of eco-anxiety (fear of environmental destruction and climate disasters) and solastalgia (distress caused by a changing environment or homeland due to deforestation, floods, etc.), especially among young people.

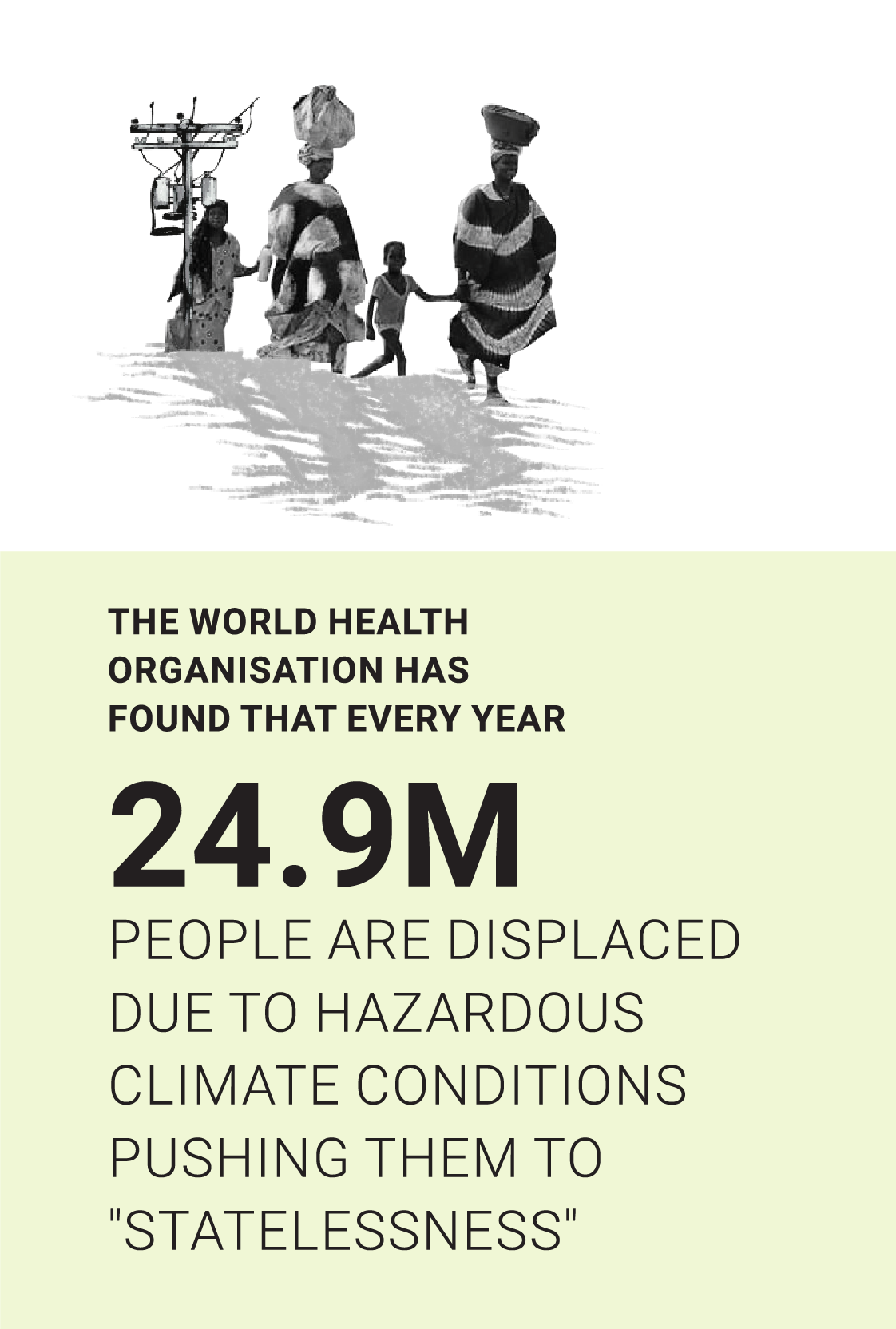

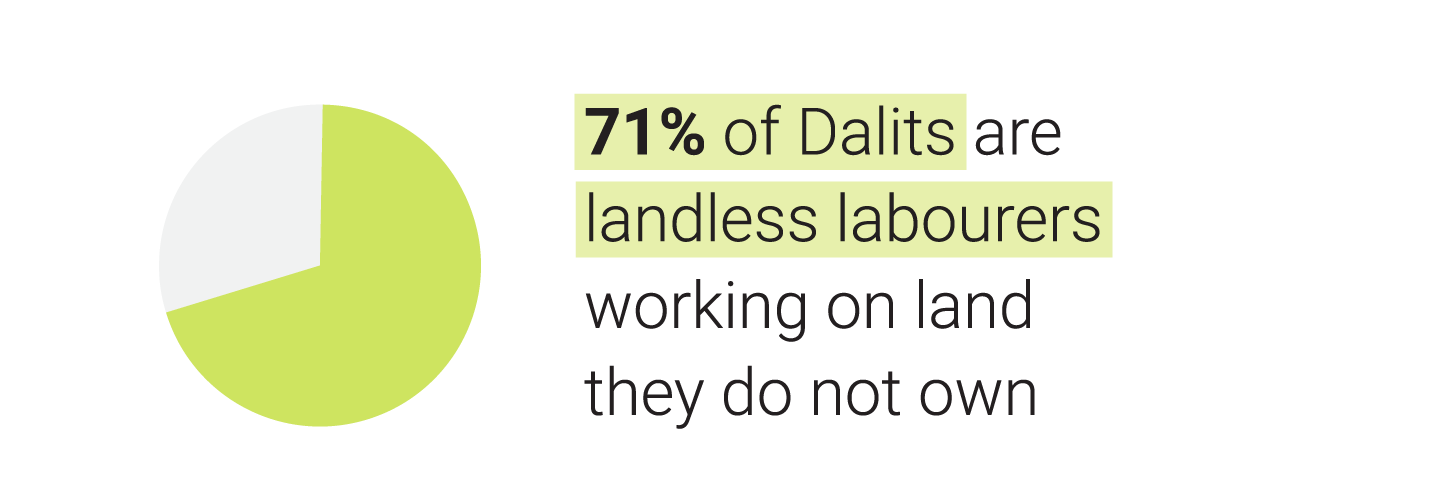

Both climate change and mental health disproportionately affect the well-being of people at the margins of society, such as indigenous and rural communities, disabled people, queer people, oppressed castes and races, and working-class communities. They also share attributes: western-dominated, expert-led, individualised discourse, deep interlinkages to systemic and policy failures, as well as structural oppressions.

ReFrame V aims to discuss such questions as: What is the need for mental health and climate change to engage with each other’s isolated discourses? Who are the stakeholders to be represented in this intersectional discourse? How do we design preventive policy and rehabilitation for climate-related distress? How do we build solidarities between the mental health and climate justice movements?

ISSUE NO. 5 DECEMBER

THE MARIWALA HEALTH INITIATIVE JOURNAL

Re-Vision

Context

Engage

Mental Health In The Darjeeling Himalaya Socio-Ecology

Memories of ‘Floods’, ‘Erosion’, and ‘Displacement’

Environmental Health and Care Require Environmental Justice

From Collective Trauma to Collective Action

Troubled Waters

Is it a Good Time to Bring a Child into this World?

Working for Disabled People’s Organisation of Bhutan